Climate policy and finance: Interplay between interest rates and the politics of emissions trading

Emission Trading Systems (ETS) are considered a fail-safe policy instrument to achieve emission reduction. Consequently, they have been implemented around the world – for example, the EU has implemented the largest emissions trading scheme as the cornerstone of its international climate policy. However, little research exists on the extent and mechanisms of the risks associated with ETS. A potential risk is if the emission allowance price rises sharply, resulting in political pressure to soften the cap. Dr. Bjarne Steffen from the ETH Zurich Energy Politics Group addressed this issue and asked: Are ETS really a safe instrument to achieve emission reduction as defined by its cap?

by Samira Amos & Tom Spencer

ETS are a policy instrument that aims at lowering greenhouse gas emissions at the lowest possible costs by allocating a limited amount of emission certificates to players i.e. forming a cap for emissions. The number of certificates allocated reflects the carbon budget of society. After each year, a company must have enough certificates to cover all its emissions. If a company reduces its emissions, it can trade the emissions certificates with others as needed or keep the spare allowances to cover its future needs (banking). Consequently, emissions are cut up to the level set by the cap where it costs least to do so. The cap is reduced over time so that total emissions fall; in the EU ETS system the cap is reduced by 2.2% every year.

Although the ETS is widely recognized as a fail-safe policy instrument, risks vary. For example, only if the cap is kept low are emissions reduced. However, the stickiness of the cap is questioned in political science literature. The cap might be softened due to political pressure if (1) emission prices reach unanticipated levels, (2) prices rise above “politically acceptable level” or (3) prices rise too sharply. The underlying mechanisms have not been studied in detail. According to Dr. Steffen, one important mechanism is feedback effects of allowance prices.

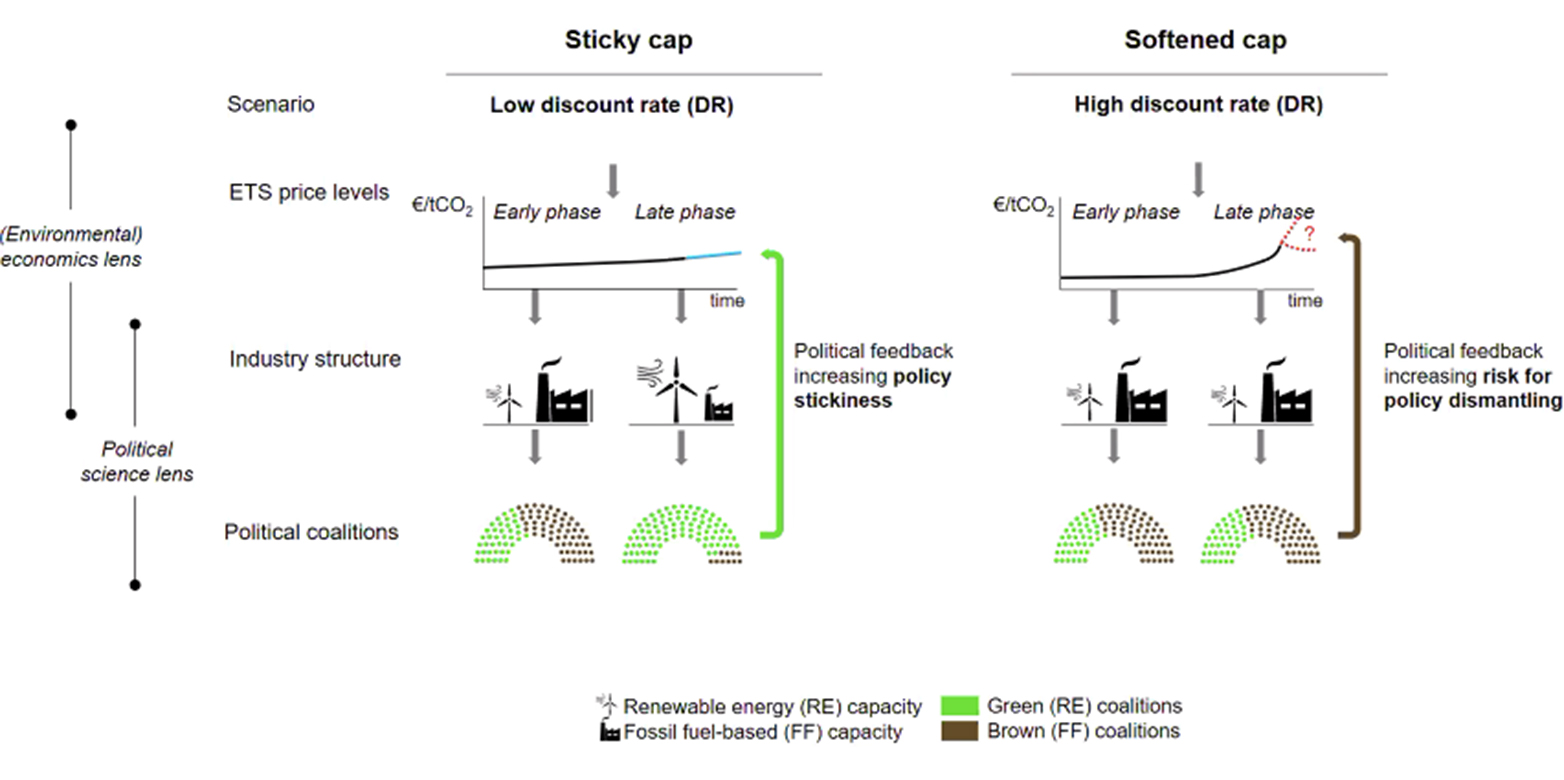

Policy feedback occurs when the impacts of a policy shape future politics. In the case of ETS, we distinguish positive and negative feedbacks, the former leading to a sticky cap and the latter to a softened cap (Fig. 1). Fundamentally, allowance prices for a defined cap rise exponentially over time, but the shape of the exponential curve is highly dependent on the discount rate of affected firms. A low discount rate favors green investment and renewable energy capacity deployment in the early stages of ETS, which over time strengthens the green political coalition that favors a "sticky cap" (positive feedback). In contrast, a high discount rate leads to a postponement of the energy transition. The price curve path characterized by a high discount rate is referred to as “hockey stick”. Such a path raises the economic adjustment cost very rapidly, creating a political backlash that softens the cap (negative feedback).

At the moment, the two main determinants of discount rate are extraordinarily low in the EU. First, the level of the general interest rates is very low because of monetary policy. If the rates increase, the cost of capital would grow and capital-intensive renewables would become more expensive. Second, the renewable energy risk premium is very low due to policies that support renewables (e.g. feed-in tariffs, quotas). However, the political support for these policies is waning. What effect does this have? And how risky is the European ETS?

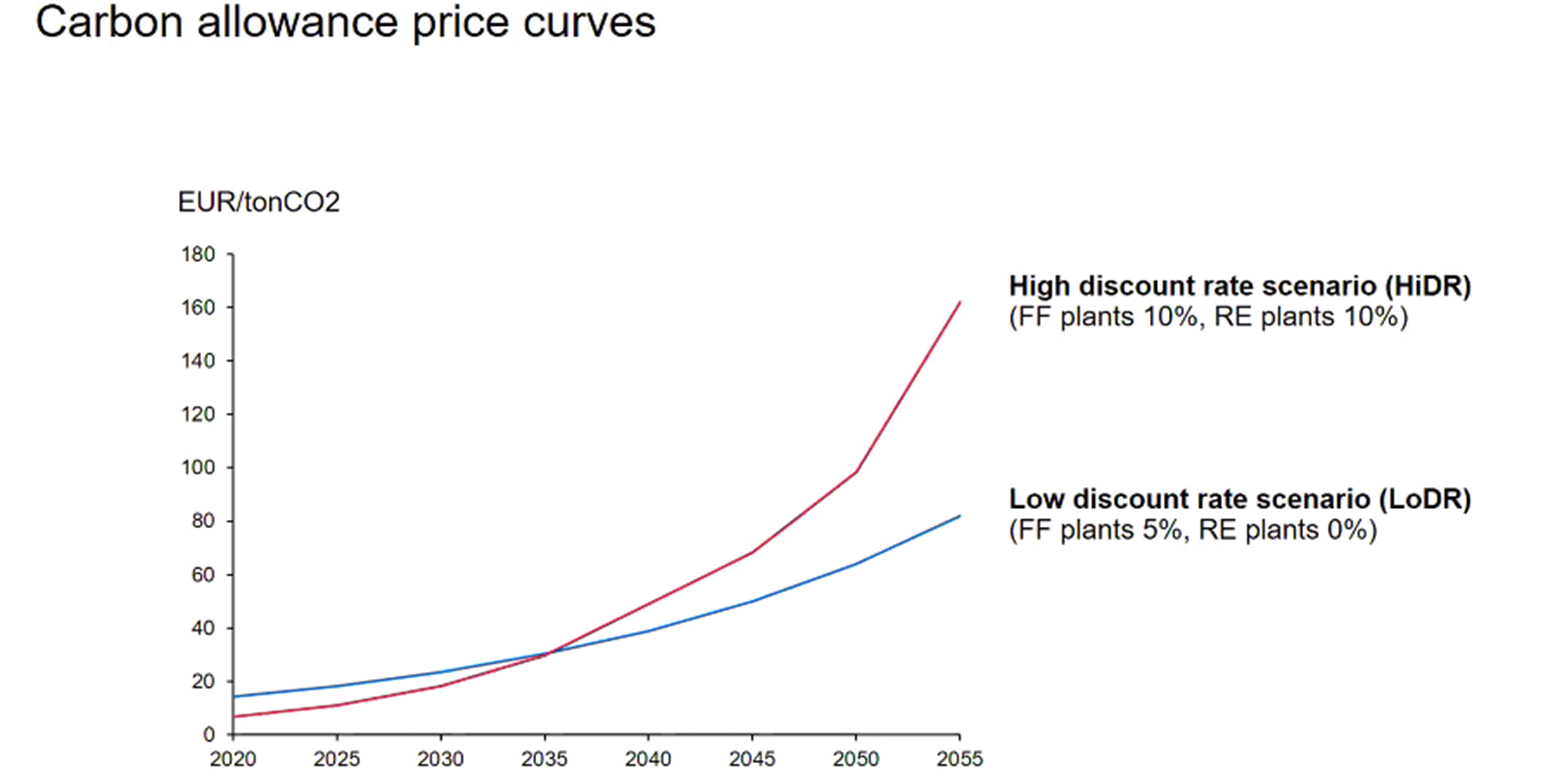

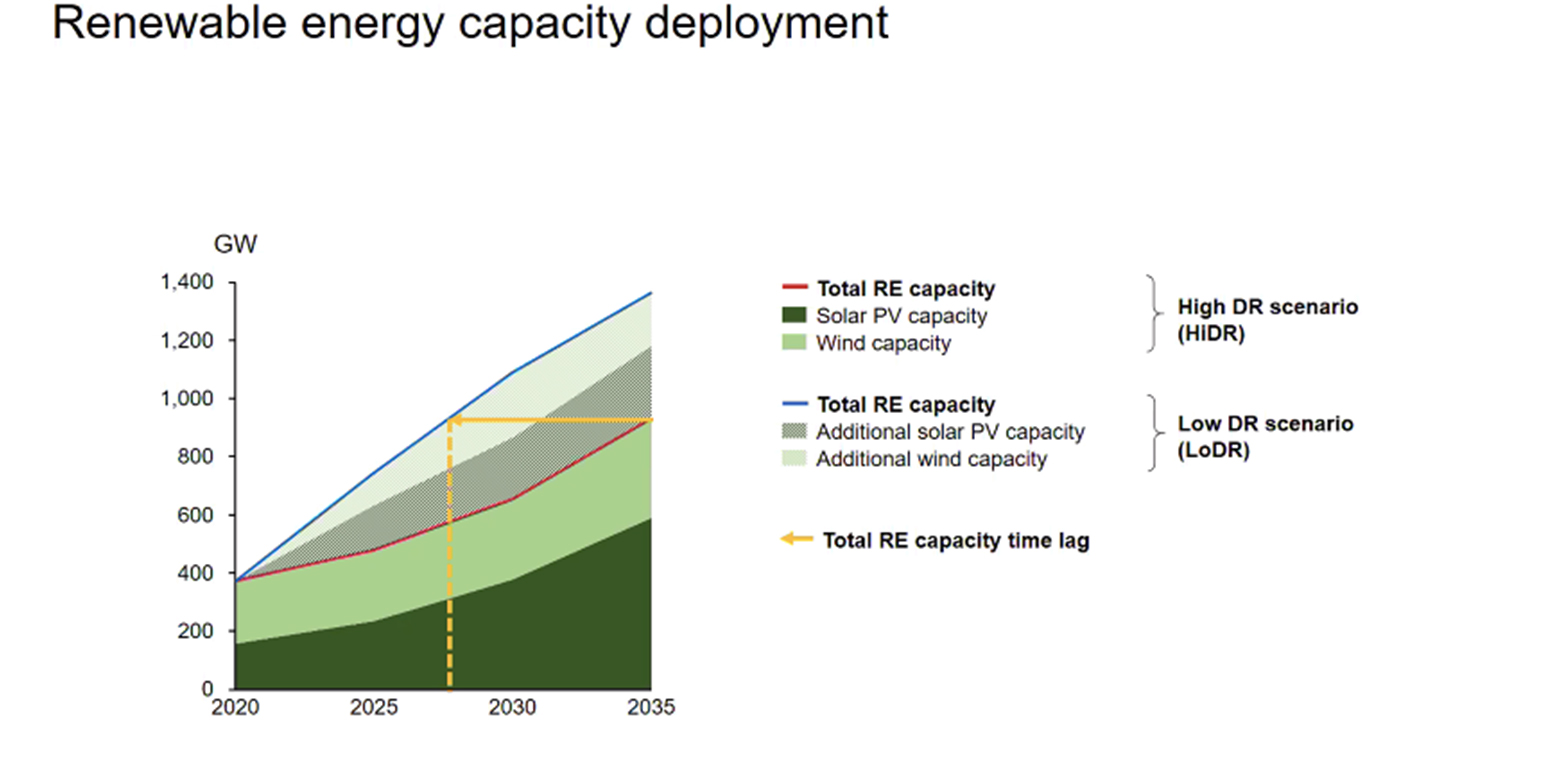

Two possible (extreme) scenarios with the same emission reduction target (EU target, 2.2% reduction per year) were modelled using the LIMES-EU model: The “Low discount rate” scenario (LoDR) and the “High discount rate” scenario (HiDR). The LoDR is based on the current situation, while the HiDR assumes that the general interest rates rise again and the renewable energy de-risking policies are phased-out. In the HiDR scenario the carbon price would be initially lower but rise relatively more and intersect with the LoDR curve in 2035 (Fig. 2). This would be the point that the risk of negative feedback, or cap softening, becomes acute. As expected, positive feedback effects dominate in the LoDR scenario, which leads to a higher capacity of installed renewable energies. Between the two scenarios we can observe an 8-year deployment time lag in the renewable energy capacity deployment (Fig. 3). Moreover, we observe high short-run profits of fossil fuel-based plants in the HiDR scenario but decreasing profits in both scenarios by 2055.

To conclude, the risk of softening the cap is considerably higher with a high discount rate because the green coalition expands much more slowly. In the case of the EU ETS, substantial political pressure on the cap could materialize by mid-2030. It is potentially significantly less costly to deal with this issue early on and prevent the hockey stick from materializing. Measures taken to prevent the materialization of the hockey stick could be (1) the continuation of renewable energy support and de-risking, (2) to keep general interest rates low or (3) to implement ETS minimum prices or price collars.

We warmly thank Dr. Bjarne Steffen from the Energy Politics group for his interesting insights into ETS and the insightful discussion!

To get a broadened sense of the ISTP and our topics of interest and past seminars visit our Colloquia page.