Counteracting shifting baselines

Anne Graupner and Thorsten Deckler founded external page 26’10 South Architects, named after the latitude of Johannesburg, in 2004 to contribute to the urban revolution of one of the most dynamic, modern and yet unequal cities in the world. Although it is becoming more inclusive and democratic, Johannesburg is still recovering from Apartheid’s segregation and experiencing rural-urban migration. As a result, many communities live in informal settlements without official approval. Rather than replacing these settlements and evicting their residents, the following ideas are at the core of 26’10 South Architects’ work: Are there housing alternatives making use of what is already there? Can we engage with the local community to understand their needs? Can informal settlements and infrastructure be improved, despite limited funds, using the local workforce and materials? Their projects reflect the socio-economic realities of Johannesburg and are centered around the local communities, with the aim of providing safe, connected and thriving living spaces. In this inspiring online ISTP colloquium, Anne Graupner from Chair of Architecture and Urban Design, Department of Architecture, ETH Zurich, showed us through several 26’10 South Architects’ projects the beauty and prospects of informality.

by Laura Mariotti & Jonathan Sedding

As an architect, it is important to often think about what matters and which position to take. Every new experience changes your perception and shapes your work. They for example quickly realised that the theory they had learned didn’t match the reality on the streets and in the rest of city. The area where their first office was located had been bulldozed at the height of Apartheid in the mid-70s, partly because it was culturally unique and had a lively street culture. To understand the potential of this area, they analysed the culture and the remaining vernacular architecture. They also engaged with the community to learn about their cultural heritage and their social and economic struggles. To exchange ideas, encourage debate and connect likeminded people, they organised monthly “Friday sessions” with urban designers, architects and community members.

If you work in a need-based environment, you have to start thinking about material resourcefulness. Environmental sustainability, carbon footprint, recycling and up-cycling waste are important aspects. It is also about finding inspiration from what is already there, to create unique moments, freely available. For instance, 26’10 South Architects built a lot of their concepts on natural light and views, using readily available materials. They found great inspiration for their projects on the side of the road during road trips in their own city. This is how the “Optic Garden” sculpture, celebrating the 2010 World Cup, was developed. The standard chevron sign was used as a ‘drawing material’ with 195 signs ‘planted’ to form an optic mass measuring 30m x 6m. Red and white patterning associated with the traffic signs was adapted to outline an iconic image of a soccer playing field, visible in its entirety only for a few seconds by drivers approaching Johannesburg.

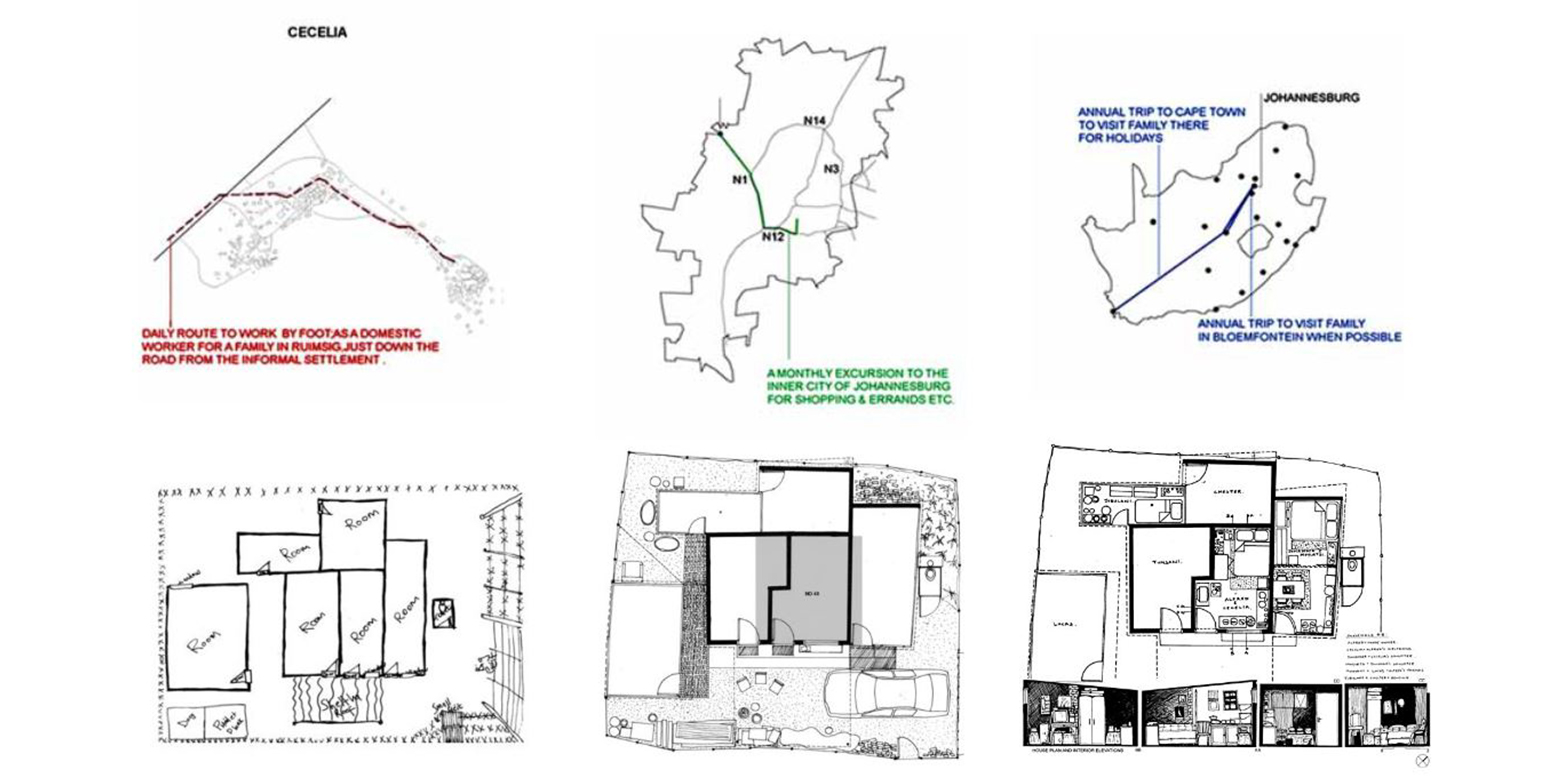

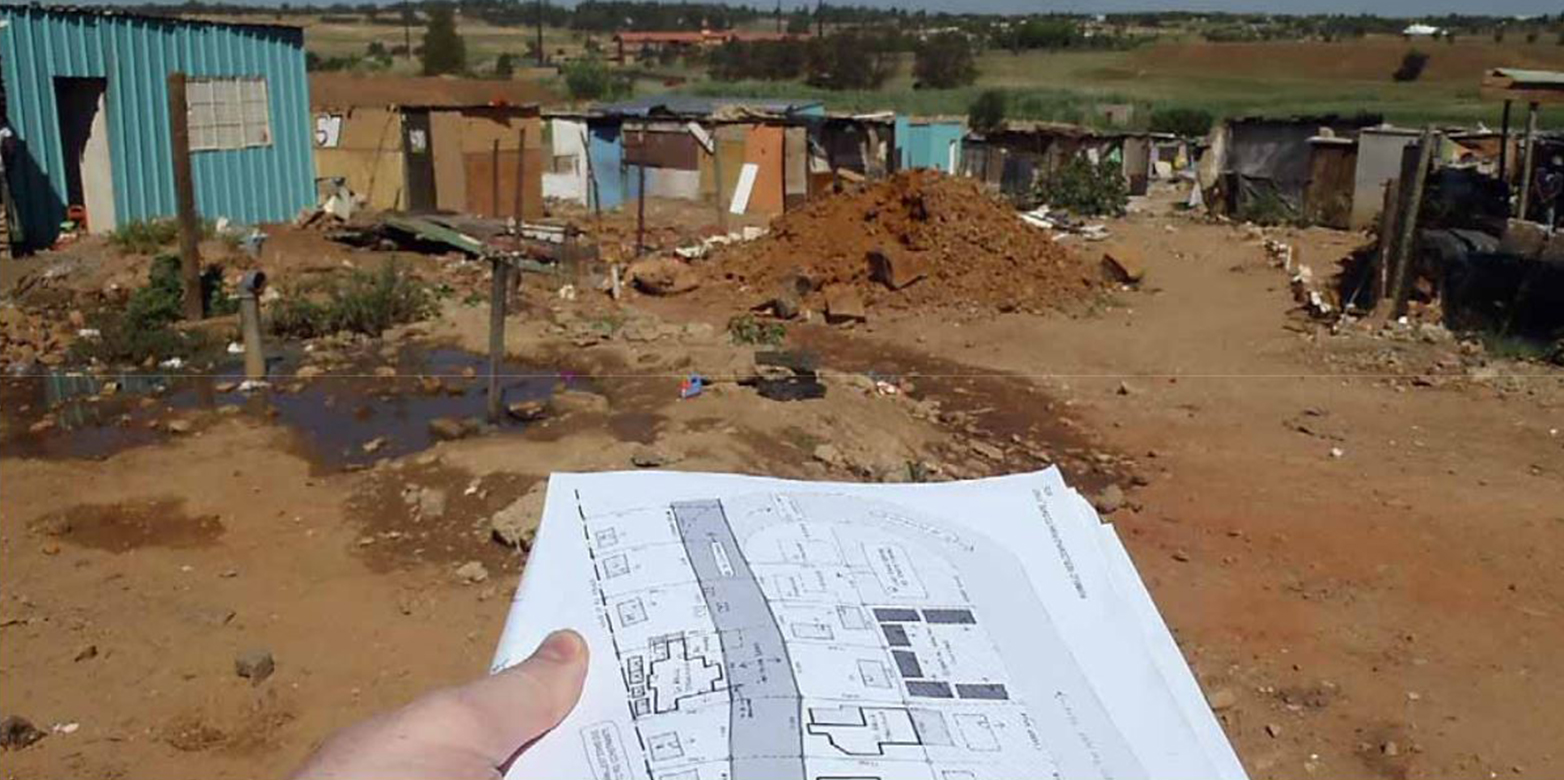

An urbanist needs to act as a designer, policy maker, educator and mediator to have an impact. When thinking about housing alternatives, we first have to understand what an informal settlement is. According to the National Upgrading Support Programme, it is a settlement without official approval; an example of spontaneous urbanism. In 2014, it was decided for the first time to map informal settlements. Accepting informal settlements as a form of housing constitutes a huge paradigm shift for the government, which used to prefer evicting residents of informal settlements to rebuild official ones. For such upgrading projects, architectural education needs to be questioned and reformed. 26’10 South Architects worked with students of the University of Johannesburg to map informal settlements and think about innovative solutions to improve them. By engaging with informality, you can see how highly complex, responsive and inventive these urban systems are.

To engage with the local communities, it is important to listen to their needs. In Soweto, the local council had limited funds to rebuild their famous Sans Souci cinema, which burnt down in 1994. After talking to the local community, 26’10 South Architects and their colleagues decided to use the ruins of the cinema as a scaffold to create an open and interactive cultural public space. Instead of rebuilding, the funds were used to organise workshops, performances and outreach projects. These events redefined the space, and this was the community’s upper goal. To the local residents, the way the space looked mattered less than what it was used for. Of course, meaningful communication communicating is not always easy and the right language needs to be found. 26’10 South Architects and their team have often used comics to show local residents what their projects were about.

In all urban cities and especially in those with high inequalities, creating everyday thriving spaces is a real challenge. Urban developers tend to focus on how many people can live in a specific area but might not think about the kind of space and living conditions they are providing. Architectural practices need to evolve based on the reality of urban environments. Although informal settlements often seem to be falling apart, they also represent unique and dynamic opportunities for innovative solutions and new policies. They are heritage sites, and strong examples of resilience, adaptiveness, and beauty.

To get a broadened sense of the ISTP and our topics of interest and past seminars visit our Colloquia page.