War Did Make States: Testing Tilly’s Thesis

Charles Tilly famously said that "War made the state and the state made war," suggesting that the modern states in Europe have been formed as an impact of Europe's violent history. Prof. Lars-Erik Cederman and colleagues from the Center for Comparative and International Studies have tested this thesis, with an initial theoretical expectation that persistently warring states are more likely to survive longer and make larger territorial gains comparing to those mostly at peace. In fact, they confirmed that warfare did contribute to the territorial expansion of European states.

In their work, they used two historical atlases (Abramson (2017) and Centennia (Reed, 2008)) on the timeframe from 1490 to 1790, as well as the Brecke dataset (1999) when it comes to evaluating conflict. Further, the thesis has been tested with three levels of analysis - systemic, state-level, and dyadic - as briefly explained below.

by Michael Andres & Marina Ivanović

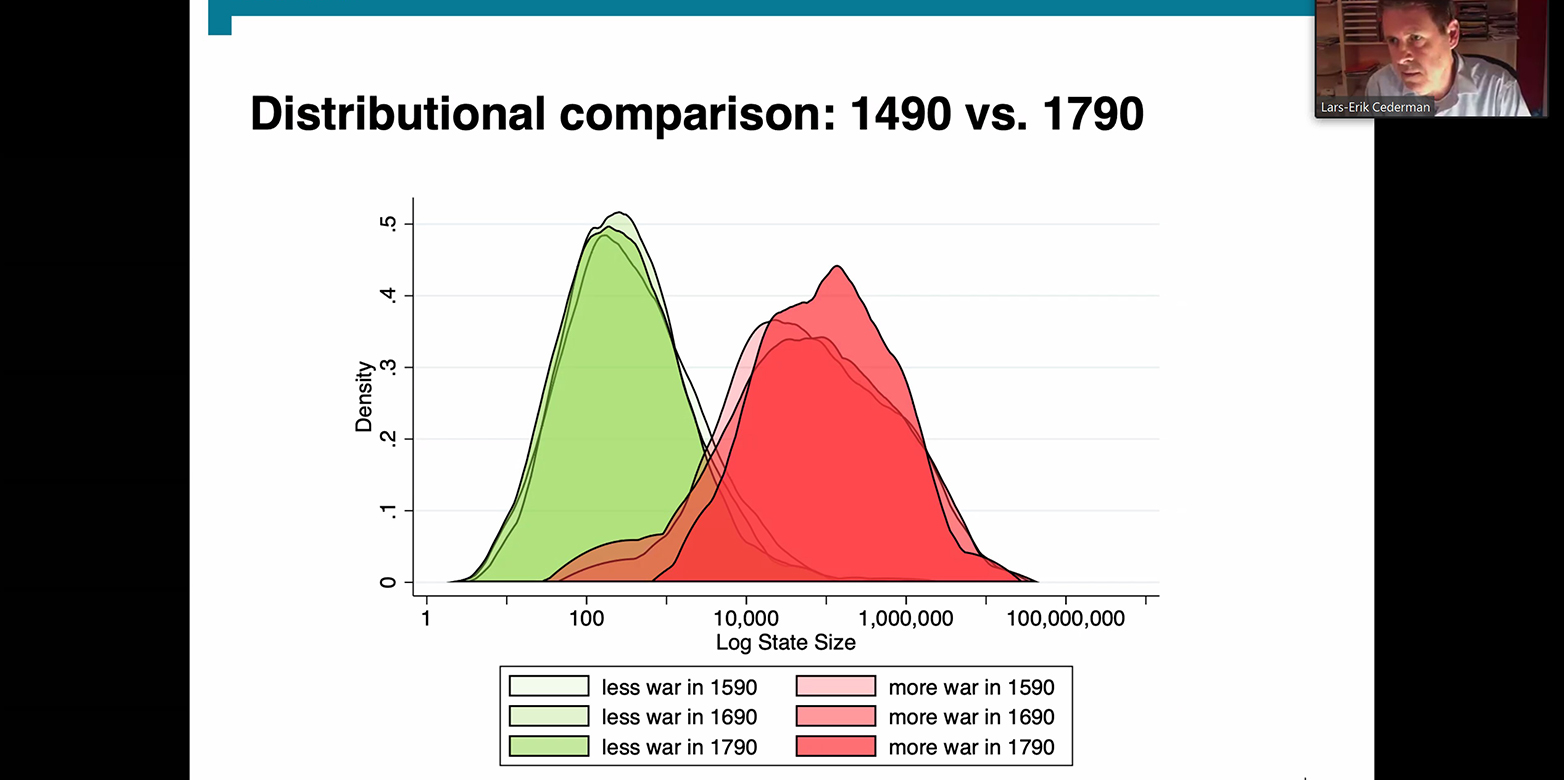

A systemic analysis is focused on the attributes of the states, such as size. Previous statistics by Abramson appeared to put doubt on Tilly's thesis. The number of states went down over time, but only by very little. As there are also major deviations for the evolution of state sizes, there is a need for a different measure to evaluate the changes' reasons and effects. For this, the 'territorial concentration' is introduced, which gives the probability of 2 random locations being in the same state. While this clearly increases, indicating states' expansion, it gives no causal relation to war preferences. When the states are divided between infliction in more or fewer wars, there is a clear difference in state sizes. Over the observed period, states which were prone to war had consistently larger sizes. This gives the first hint in support of Tilly's thesis but needs more detailed analysis, as this aggregated data does not allow causal explanations.

In the state-level analysis, states' growth has been traced over time, specifically distinguishing gaining territory during peacetime and as a consequence of war. Here, some influential states have been traced, particularly Prussia, France, the Habsburg Empire, Russia, and Sweden. The time period from 1490 to 1790 has been observed using the Abramson and Brecke sources, as mentioned before.

For instance, Prussia's growth was mainly peaceful until roughly 1650, when they almost got eliminated by Sweden. However, after that period, their solid expansion was war-related. On the other hand, France didn't have a huge expansion relative to their initial size, but it's important to mention that they experienced substantial growth before 1490. In the Habsburg Empire case, professor Cederman mentions that there is a famous idea that they didn't fight, but only were clever in the territorial acquisition. However, in this research, it is shown that their expansion is largely related to war.

Nonetheless, we can observe another important way of territorial gain - Terra Nullius - which is related to conquering uninhabited areas or those not claimed by any state. For instance, Russia is a good example of a state that mostly got expanded in this way, along with the warring. And finally, there are some states whose overall result was not an expansion but rather a territorial loss, as can be seen in the case of Sweden.

Furthermore, professor Cederman and his research team studied states' death as a part of this analysis. Abramson did this as well, arguing that it could be used as a justification of Tilly's theory. They conclude that the smaller the state, the bigger their hazardous rate is at warfare.

For the dyadic analysis, combinations of two states are considered. It is checked whether they interacted peacefully or through war and how big the respective expansion was. As a result, ‘war dyads’ had significantly higher size gains than the peaceful ones. After controlling for matching effects, it turns out that territorial gains relate to war but not to peace dyads. Unsurprisingly states that engaged in war more often also had a higher probability of having changing borders. Looking at peace agreements, there is a clear increase over the years from 1490 to 1790. In the last 100 years, there have been nearly no resolutions without a peace agreement.

Taking a further look at the territorial concentration, there is an increase between 1800 and the first world war, displaying even further expansions, which are not covered in the presented paper. Additionally, at this time, there is also a rise of nationalism, which becomes the driving factor between the state interactions.

The systemic, the state-level, and the dyadic analysis all seem to support Tilly’s Thesis. There are clear correlations between war activity and state expansions. Looking at specific states, we see a trend of expansion led by war-making. And states which interacted through war also had bigger size gains than peaceful dyads. But other factors are also clearly relevant, as some states make significant size gains with pacific expansions. The effect of Darwinism also cannot be neglected.

Nationalism started to become an important influence on the observed states and thus has to be considered for all future analyses and the whole internal dimension of states, which was not part of the paper presented.

To get a broadened sense of the ISTP and our topics of interest and past seminars visit our Colloquia page.