Escaping the Fly Room

In shaking our society to its core Covid-19 shows that we must adopt a far broader perspective to tackle the complex socio-ecological problems humanity faces, says Jaboury Ghazoul, associate members of ISTP. (Re-post from ETH Zukunftsblog)

Living in a complex world

The global mayhem triggered by Covid-19 shines a light on interconnectivity, and the need for interdisciplinary integration. The virus is possibly a consequence of the illegal wildlife trade, driven by inequalities of wealth and opportunity, cultural traditions, and ineffective law enforcement. Highly urbanised societies have facilitated rapid viral spread through transportation networks connecting global cities.

Lockdowns have consequences that transcend epidemiology, affecting employment, mental and physical health, and domestic abuse. A global economic downturn will increase poverty, while existing inequalities will be exacerbated, setting the scene for social conflicts and strife in the coming years. Covid-19 reminds us that in a complex and interconnected modern society, perturbations cascade along many pathways, driving multiple outcomes that are difficult to anticipate and plan for.

Overcoming disciplinary thinking

This is typical for so called ‘wicked problems’ where even agreeing on the nature of the problem is challenging, and where response actions create new unanticipated problems in other sectors. Covid 19 and our collective responses to it exemplifies a wicked problem. Climate change, species extinction, and environmental degradation are further examples.

Their diversity and complexity suggest a need for alternative understandings that transcend disciplinary boundaries. By only studying individual components, we neglect that these parts behave differently when isolated from their environmental context. Reductionist approaches that isolate components for experimental enquiry can thus provide only selective understanding.

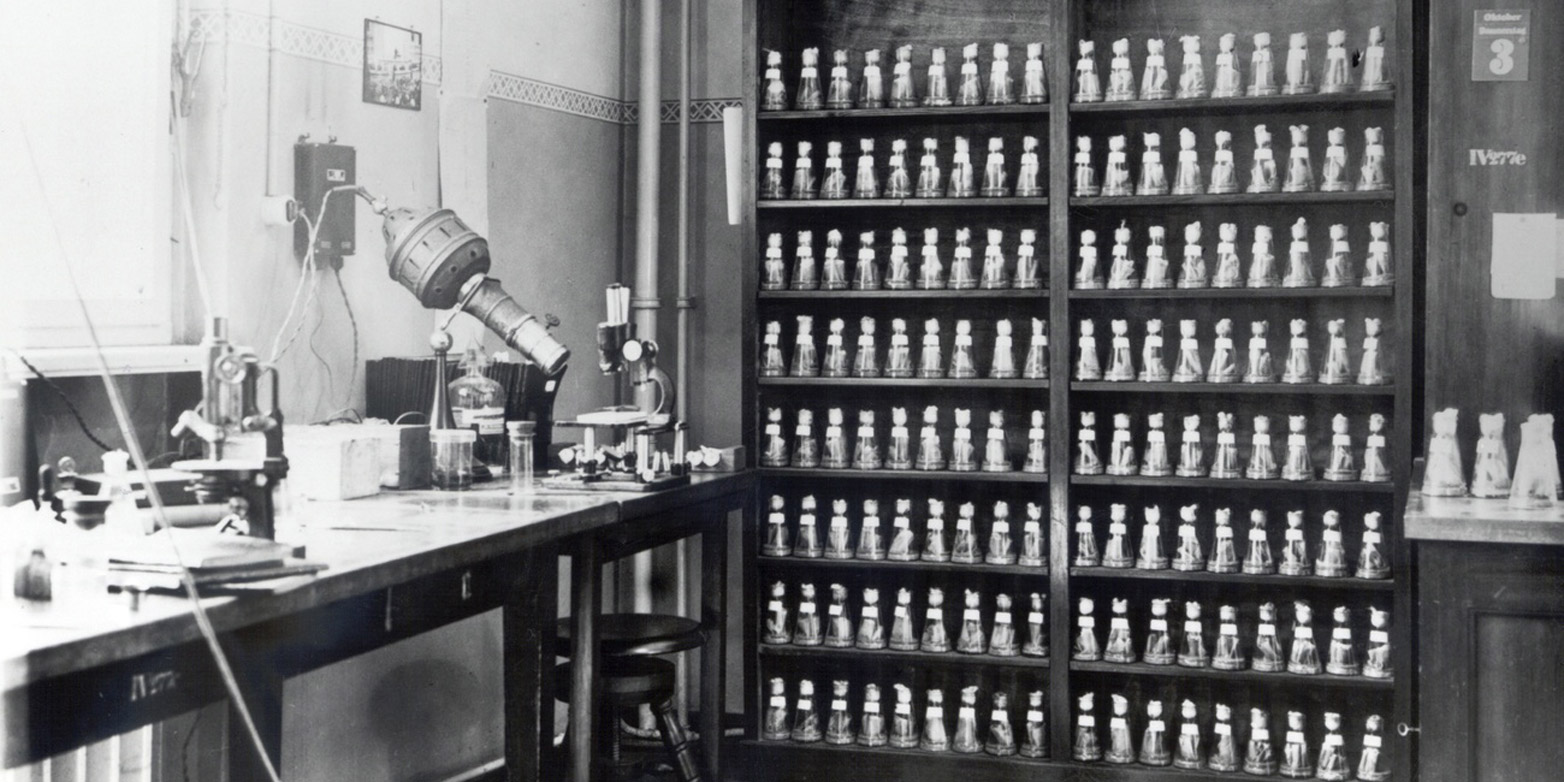

"It is time to escape the rigid reductionism of Morgan’s Fly Room."Jaboury Ghazoul, ETH Prof.

The lesson to draw is this: If we want to adequately deal with these challenges we need to embrace a broader ‘systems’ approach to our work and lives. Systems thinking will not deliver immediate answers to this conundrum, because complex systems continually change. Yet social and political structures organised around systems approaches can foster adaptive change.

Despite much current interest in systems thinking, it has yet to be mainstreamed in educational curricula, governmental organisation, and societal structures. Academia should be at the forefront of innovative systems thinking, yet remains grounded in decidedly disciplinary streams. Transdisciplinary centres encompassing systems approaches are rhetorically celebrated, yet remain marginal to departmental interests, as evidenced by resource allocation and reputation. Covid-19 suggests that this needs to change.

Further information

The author points out a historical quote that matches well with the meaning of this post:

In The Conduct of Life (1951), Lewis Mumford wrote: "So habitually have our minds been committed to the specialized, the fragmentary, the particular, and so uncommon is the habit of viewing life as a dynamic inter-related system, that we cannot on our own premises recognize when civilization as a whole is in danger".

- For further information and the full article, please visit the ETH Zurich homepage.